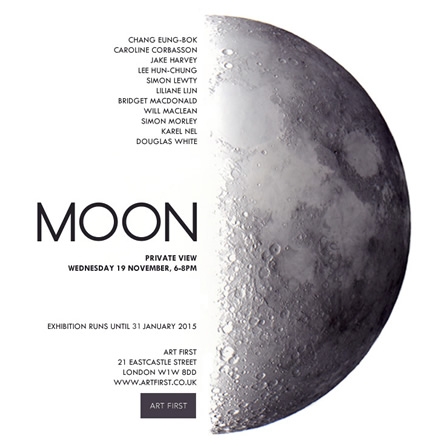

Main Gallery

Moon

19 November 2014 - 1 February, 2015

Artists

- Chang Eung-Bok

- Caroline Carbosson

- Hun Chung Lee

- Jake Harvey

- Simon Lewty

- Liliane Lijn

- Will Maclean

- Bridget Macdonald

- Simon Morley

- Karel Nel

- Douglas White

It isn’t surprising that the moon has always fascinated mankind. It is the largest and brightest object in the night sky, and unlike the sun has a different shape every day. But in the West the moon has faded from the imagination, where it once shared symbolic honours with the sun. The same thing is happening in the East, thanks to Westernisation and globalisation, although East Asia countries still adhere to the lunar calendar, celebrating New Year on the second new moon after the winter solstice, with the result that their new year shifts confusingly between late January and early February.

In Greek mythology, Selene (in Latin, Luna) was the goddess of the moon, also called Phoebe, as she was the sister of Phoebus, the god of the sun. Often she was depicted riding side saddle on a horse or in a chariot drawn by a pair of winged horses. Selene's great love was the shepherd prince Endymion, granted eternal youth and immortality by Zeus and placed in a state of eternal sleep in a cave near the peak of Mount Latmos. Silene descended to consort with him in the night.

Today, however, Westerners think not so much of Silene as of the ‘man in the moon’, or the American men on the moon. In East Asia they still think of the rabbit. One version of the legend is that there was once a village where lived a rabbit, a fox, and a monkey. The three devoted themselves to the Buddha, and one day the Emperor of the Heavens decided to test their faith. He told them to bring him something to eat. The three set off to fulfil his wish. The fox returned with some fish, the monkey with some fruit, and the rabbit, who could do nothing but bring back some grass, lit a fire with it and jumped in, offering his own self as food. Such commitment earned the approval of the Emperor, and henceforth the rabbit was placed in the moon as its guardian, with “smoke” surrounding him as a reminder of his efforts.

East and West agree that the moon brings forth warm and empathetic emotions. ‘Queen of the stars!–so gentle, so benign’, writes William Wordsworth in To the Moon. Often, it leads to thoughts of the beloved. The Japanese poet Yakamochi (737–785) writes:

When I see the first

New moon, faint in the twilight,

I think of the moth eyebrows

Of a girl I saw only once.

Thus the moon also makes us melancholy. The Chinese poet Tu Fu (712–770) sits in a far flung province and remembers his distant brothers, lamenting that ‘The moon is just as bright as in my homeland’.

In Zen Buddhism, Enlightenment is often likened to the moon shining brightly in the dark sky, its teachings are a finger pointing up towards the moon. But the illusory nature of being is also likened to the moon reflected in water. The Zen monk Hakuin (1686–1788) appended the following poem to a painting:

The monkey is reaching for the moon in the water,

Until death overtakes him he will never give up.

If he would only let go the branch and disappear into the deep pool,

The whole world would shine with dazzling clearness.

In the Catechism of the Roman Catholic Church it declares: ‘The Church has no other light than Christ’s; according to a favorite image of the Church Fathers, the Church is like the moon, all its light reflected from the sun’. But for the Christian solar-inclined imagination, a darker significance surfaces: the moon’s nocturnal habitat is also Satan’s. By moonlight witches cavort. Thus in the West there is a deep tradition that casts the moon as a destabilising, negative force. Feeding on this cultural legacy, in the heated imagination of the ‘Gothic’ the full moon brings forth werewolves. The moon also encourages depravity. It is deathly and deadly. In his poem Annabel Lee, Edgar Allen Poe brings the moon’s erotic and thanatopic capacities together:

For the moon never beams, without bringing me dreams

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee;

And the stars never rise, but I feel the bright eyes

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee;

And so, all the night-tide, I lie down by the side

Of my darling—my darling—my life and my bride,

In her sepulchre there by the sea—

In her tomb by the sounding sea.

The moon makes us so melancholy that it can drive us mad—hence the word ‘lunatic’. Women were especially susceptible. In The Moon and the Yew Tree, the American poet Sylvia Plath writes:

The moon is no door. It is a face in its own right,

White as a knuckle and terribly upset.

It drags the sea after it like a dark crime; it is quiet

With the O-gape of complete despair.

In modern-day Wicca paganism the moon eclipses the sun in importance: ‘The Moon phases create energies that affect us perhaps as much as its gravitational pull does’, writes Erin Dragonsong on her website. ‘So understanding the phases of the Moon becomes crucial in working magick. In fact, the Moon’s power to affect all living beings is astounding, even though it is barely acknowledged, even by many Pagans.’

Carl Jung, seeking to synthesize world traditions, considered the moon to be a key symbol of the unconscious, of intuition, creativity, the anima, the mother, and the feminine in general. The sun, in contrast, is the masculine principle, the lucid and clear realm of logic and reason from whose perspective the moon is just the natural satellite of the earth, made visible at night chiefly by the sun’s reflected light. Jung was at pains to emphasise that in order to achieve the truly healthy ‘individuated’ mind it was essential for modern men and women to allow themselves the time and space in which to explore the rich store of symbols our collective imagination over millennia has created. ‘On my many travels I have found people who were on their third trip around the world— uninterruptedly. Just traveling, traveling; seeking, seeking’, said Jung in a seminar given in 1939:

I met a woman in central Africa who had come up alone in a car from Cape Town and wanted to go to Cairo. ‘What for?’ I asked. ‘What are you trying to do that for?‘ And I was amazed when I looked into her eyes—the eyes of a hunted, a cornered animal—seeking, seeking, always in the hope of something. I said, ‘What in the world are you seeking? What are you waiting for? What are you hunting after?’ She is nearly possessed; she is possessed by so many devils that chase her around. And why is she possessed? Because she does not live the life that makes sense. Hers is a life utterly, grotesquely banal, utterly poor, meaningless, with no point in it at all. If she is killed today, nothing has happened, nothing has vanished—because she was nothing! But if she could say, ‘I am the daughter of the Moon. Every night I must help the moon, my Mother, over the horizon’—ah, that is something else! Then she lives; then her life makes sense, and makes sense in all continuity, and for the whole of humanity. That gives peace, when people feel that they are living the symbolic life, that they are actors in the divine drama. That gives the only meaning to human life; everything else is banal and you can dismiss it.

In one way or another the works in this exhibition evoke the multi-faceted symbolism of the moon, its power to move us. The artists use a wide range of styles and media, traditional and not so traditional. Even in an age when science and technology seems to have relegated it to the margins of the mind, they are testimony that the moon continues to exert its influence upon the imaginations of both the East and West.

Simon Morley